The love affair between humans and mushrooms dates back tens of thousands of years, long before the dawn of history. It's likely that even the earliest hominids, who first stood and walked on two legs, had a complex relationship with mushrooms—some they learned to avoid the hard way, while others, including wild varieties of shiitake, were incorporated into their diet as hunter-gatherers. Others still were probably utilized in different ways.

But let's focus on the most beloved Japanese mushroom of all—the shiitake.

Often referred to as a "Japanese mushroom," the shiitake does indeed grow wild in Japan. Having evolved about 100 million years ago (long before us, and as things stand today, it will likely outlast us as well), it’s safe to assume that the first nomadic gatherers who reached the Japanese islands were familiar with it.

However, wild shiitake also grows in China, Indonesia, and other Southeast Asian countries. In these regions too, shiitake has long been known as an excellent edible mushroom, with some areas inhabited by humans even before they reached Japan.

Interestingly, the first recorded instance of cultivated shiitake dates back to 1209 in China, leading to the widely accepted theory that shiitake was introduced to Japan as a cultivated crop from China. Much like tofu, the 'Japanese eggplant,' and many other innovations, the Japanese adopted it, added their unique twist, and made it their own.

But before we delve into shiitake cultivation techniques—an important topic, which I’ll get to shortly—let’s first understand what makes this mushroom so special. Shiitake offers the ultimate combination for an edible mushroom: it's both incredibly delicious and highly nutritious.

Shiitake is a classic cap mushroom, rich in protein—high-quality protein, in fact, especially compared to other plant-based sources (and yes, I know mushrooms aren’t classified as plants) shiitake contains 7 of the 8 essential amino acids.

Moreover, shiitake has been recognized as a medicinal mushroom since ancient times. Modern research confirms that shiitake has antiviral and antibacterial properties and can positively impact blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

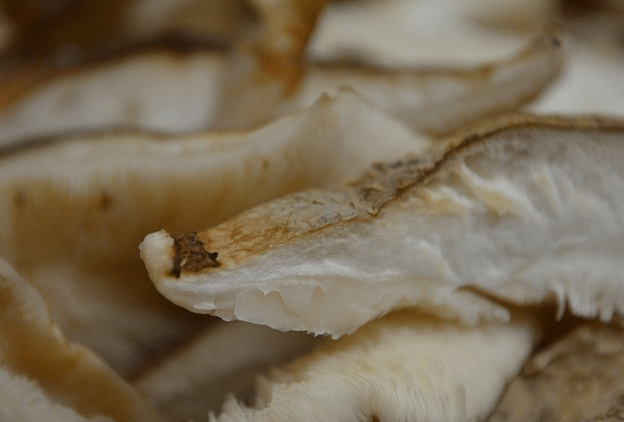

So, why was it so difficult to find fresh shiitake mushrooms in Israel until recently? Remember when I promised to return to cultivation methods? Well, here we go. A detail I haven't mentioned yet is that shiitake mushrooms grow on tree trunks (even along live trees and on logs and stumps). Primarily oak trees. In Japanese, the name "shiitake" means "oak mushroom."

This trait made domestication challenging. The method developed by the Chinese (as mentioned in the 1209 Chinese document) involved finding areas where shiitake mushrooms grew naturally, scattering many cut oak logs, and hoping that some of the spores released by the mushrooms would take root in the wood and start a new life cycle.

This method worked fairly well, but it still limited shiitake cultivation to traditional growing regions until the late 19th century.

Today, shiitake is the second most widely consumed edible mushroom globally, after the common mushroom we know as champignon (in its light form) and portobello (in its dark form). How did this happen? How is it that in Israel, a country where, until a few years ago, you could only find dried, imported shiitake, you can now find fresh, locally grown shiitake—even organic varieties, like the wonderful shiitake waiting for you this week in the store?

We owe thanks to the Japanese, specifically Japanese scientists, who since the 19th century have developed advanced, user-friendly cultivation methods that allow for the transfer and propagation of shiitake spores even on sawdust substrates. This has made shiitake a common agricultural crop worldwide.

What to do with it? The same as with any delicious mushroom—add it to salads, quiches, soups, omelets, pasta, stir-fried vegetables, or just about anything you like.