The myth of Prometheus in Greek mythology can be analogous to the story of eating from the Tree of Knowledge in Genesis.

In a sense, both these myths aim to explain the wonder of human evolution. The story of the Tree of Knowledge (for which I have my own subversive interpretation, I shared in a newsletter about mushrooms), is about granting human intelligence. The Prometheus myth is more indirect, as it focuses on the discovery of fire, but the end result is the same: a conscious awakening that allows us to develop, different from other animals.

According to the myth, Prometheus, a half-god and half-human, stole fire from the temple of Zeus on Mount Olympus and gave it to humans. At this point in the story, you're probably scratching your head and asking yourself: "What on earth is she getting at? This is a vegetable newsletter and she promised to talk about fennel?"

Well, when Prometheus climbed Olympus to steal the fire, he brought with him a dry stalk of fennel. He lit this stalk from the eternal flame that burned on Olympus (if you've ever wondered where the tradition of lighting the Olympic torch comes from, that's where). And so, humans acquired fire.

Prometheus' fate was less than pleasant. Zeus chained him to a rock, and every day an eagle came to eat his liver, with no anesthesia.

This story doesn't teach us much about fennel, but we can learn from it about the commonality of this plant for the ancient inhabitants of the Middle East. Wild varieties of this Apiaceae memeber, with its yellow umbrella-shaped inflorescence, are still common near the shores of the Mediterranean and have been used by humans for at least 4,000 years.

When I say "used by humans" in the context of fennel, it's worth noting that the earliest mentions of it are in the context of a medicinal plant. Hippocrates, the father of medicine and author of the Hippocratic Oath, attributed many virtues to fennel, including a solution for the bite of a rabid dog.

Personally, I wouldn't try that at home. On the other hand, even modern medicine recognizes that fennel has anti-inflammatory therapeutic value and is effective in relieving digestive problems and even eye problems.

The wild varieties, which our ancestors encountered, didn't have the bulbous root that we enjoy today, but they too were characterized by an elating anise aroma, and their leaves, flowers, and seeds were edible.

So, in addition to being a medicinal plant, fennel began to be used as a spice and at some point, after being domesticated, new varieties were developed, such as that with the bulbous root that we know and love today.

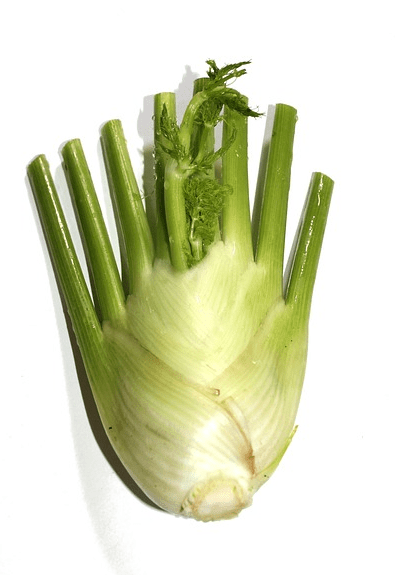

So let's talk about this root and what we can do with it. I love fennel even in its raw and tough version. A little lemon juice on top and I can happily munch on it.

Of course, it also works in salads and cold plates, but it's wonderful when roasted, and it fills with rich flavors and an almost meaty texture. Now, as we approach the peak of winter, fennel is truly at its best.

Yes, I know there are those who don't like the anise flavor of fennel. I have nothing to say in your defense. If, in the case of cilantro, you can justify your aversion to the taste through your genetics, in the case of fennel and anise, that excuse doesn't hold up.

You're simply missing out. Indeed, it is an acquired taste, that should definitely be acquired (you don't have to try hard, it's already in the weekly box).