I know I've mentioned the wild cabbage and its modern brassica descendants countless times. Since we have purple kohlrabi in our box this week, one of the family's less common members, I'll address this topic again. But this time, I want to highlight a different, fascinating point.

As I've mentioned many times, botanically speaking, all members of this family – including cabbage, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, and kohlrabi – are essentially the same plant.

This claim might sound absurd when you compare cabbage to broccoli or kohlrabi. After all, they don't even look alike. So how could that be?

I've mentioned before that this has to do with us, humans, and a process called domestication and cultivar development. To modern ears, this process may sound rather scientific, but it's actually a principle called Artificial Selection.

To fully understand the concept of artificial selection, it's worth first recalling the process of natural selection, which was based solely on natural selection. One of the characteristics of plants is that their mutation rate is very high, and it's not uncommon for genetic material to move from one place to another, creating a new appearance or highlighting a different trait.

In almost every new generation, we encounter some plants that have undergone some kind of change (size of leaves or flowers, higher or lower sugar content, color change, roots, etc.). In other words, evolution shoots in all directions all the time, and the natural selection takes its turn.

A small portion of these mutations prove beneficial for the plant. For example, if a mutation appears that adds thorns to the plant, and the thorns deter birds that like to eat its fruit, it's likely that this mutation will survive in the next generation. Within a few generations, all the plants in the same environment will be descendants of the plant with the mutation, while the plants without thorns will disappear because there is a kind of "negative selection pressure" on them that only grows from generation to generation, as the birds avoid the thorns and eventually the thornless variety will become extinct.

This is also why typically wild varieties are fundamentally different and less attractive to humans (and other animals) than domesticated varieties, which are rich in sugar, have large fruits, or wide leaves. There's no doubt that mutations of all these types appeared in nature many times – they simply didn't survive and became extinct because they were eaten or were not energetically efficient (a plant with a genetic code to develop large fruits would have difficulty mobilizing the energy resources needed to survive over time in nature).

This is where we come in, actually our ancestors who brought about the agricultural revolution ten thousand years ago. A revolution that can be summarized with the term I mentioned at the beginning: "artificial selection."

As mentioned, if a cauliflower had popped up in a natural wild cabbage patch as a result of a mutation, it would probably have been devoured by a lucky rabbit. But imagine if the person who encountered the strange vegetable realized that for him, this vegetable could be very attractive?

He would protect it from all harm and try to propagate it, hoping that some of its offspring would duplicate the mutation. He would try to give it growing conditions that would keep pests away and give it the energy it needed. Thus, more or less (because it is usually a long process that takes several generations, during which the most successful individuals are isolated), new vegetable varieties come into the world.

When did kohlrabi first appear? Opinions differ. Some believe that varieties of cabbage with a bulb (as opposed to the common belief that it's a root) were already developed in Roman times, but the truth is that we don't really know.

The first certain record of kohlrabi in history is from a text by an Italian botanist in 1554, who reports that it is a new vegetable in Italy (a detail that clearly undermines the Roman hypothesis). In any case, from around this time, we find kohlrabi throughout northern and central Europe (the name originates in German and literally means "cabbage root") as a beloved and tasty vegetable.

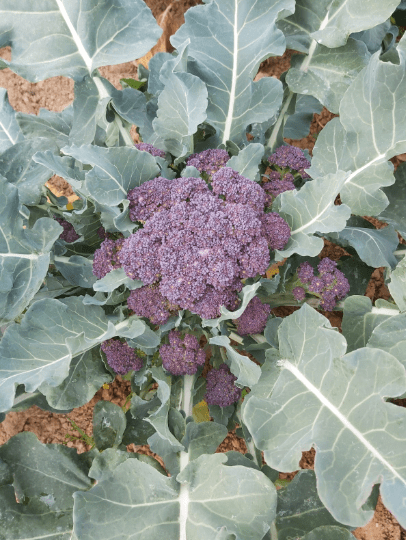

In recent decades, its luster has faded, which is a shame. Because it's wonderful in stews, and I also love it cut into small cubes fresh (sprinkle with a little coarse salt and it's a delicacy), especially when I happen to come across its purple variety, which is relatively rare.